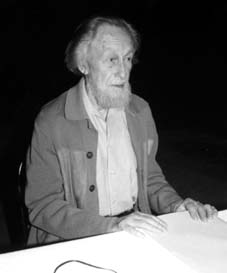

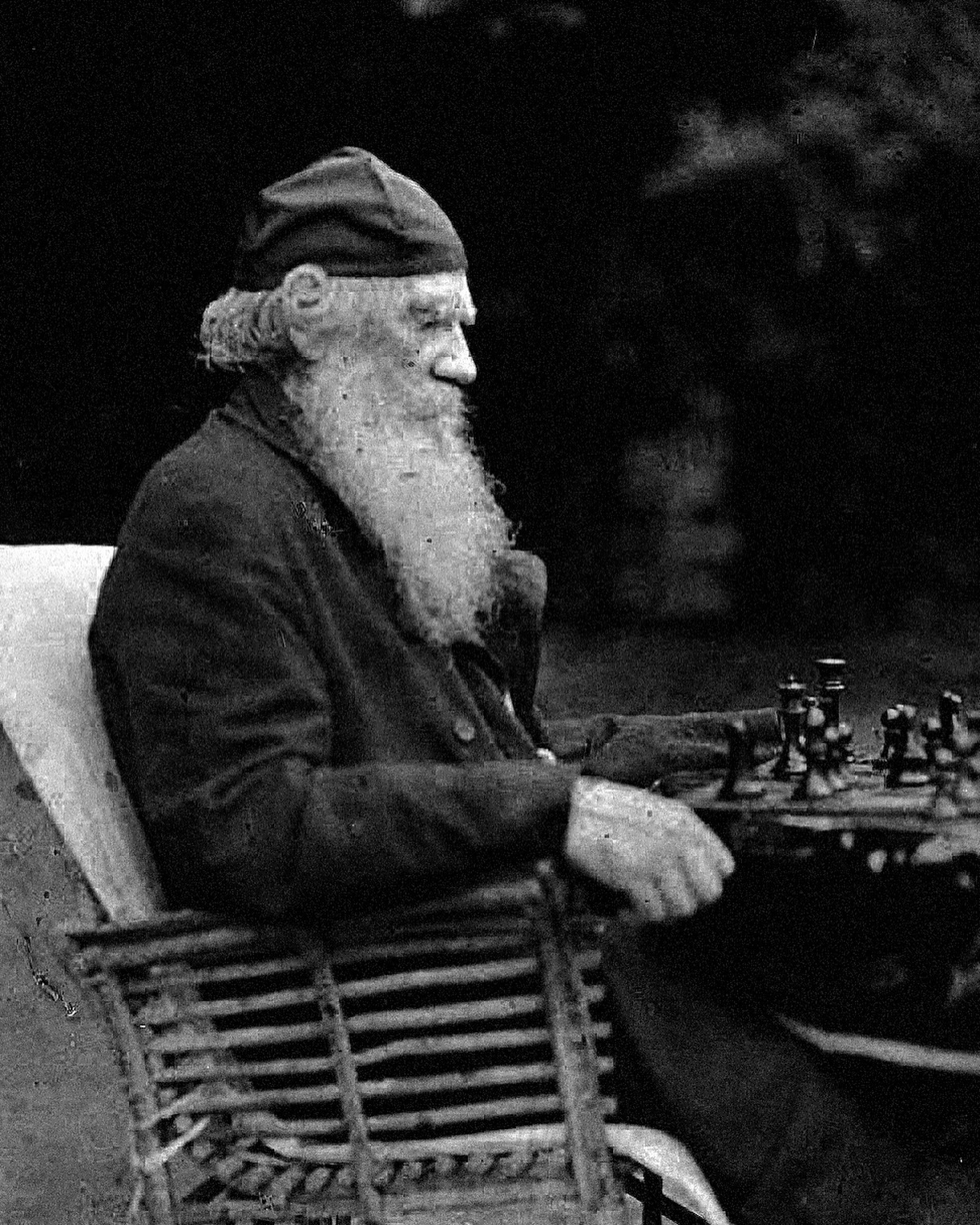

An account of the Martin Lings Centenary Lecture delivered by Dr Reza Shah Kazemi at the Royal Asiatic Society, November 28, 2009

The Royal Asiatic Society auditorium was filled to capacity with people who had come to hear the third and final lecture in commemoration of the centenary of the birth of the late Dr Martin Lings. As the clock approached seven, those who had been unable to secure tickets before they sold out were ushered in, relieved not to have been turned away. The white marble statue of Sir Henry Thomas Colebrooke, founder of the Royal Asiatic Society, gazed impenetrably at the audience as Emma Clark introduced Dr Shah Kazemi on behalf of the Matheson Trust and the Temenos Academy, co-sponsors of the event.

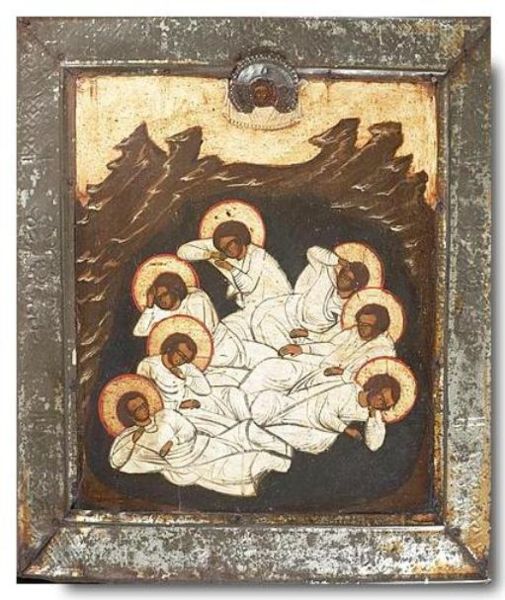

There is perhaps no one better qualified to deliver the talk than Dr Shah-Kazemi, a long time friend, student and disciple of Dr Lings who was also his next-door neighbour for fifteen years. He delivered an account of Dr Lings —Shaykh Abu Bakr Siraj al-Din as he is also known— that was at the same time intimate, objective, and illuminating. Dr Shah-Kazemi centered his talk on the notion of spiritual sincerity (sidq in Arabic) and illustrated how Dr Lings was the perfect embodiment of this sincerity in every aspect of his life — his mind, character and heart. The leitmotif of the talk was one of Dr Lings’s poems, “Self Portrait,” in which he apparently laments his birth, so late in the historical cycle, that prevented him from witnessing first-hand the prophets and avataras of the great religions, including King David, Krishna, Jesus, the Buddha and the Prophet Muhammad. But the poem ends with the stirring lines:

No more I say: Would it had been!

For I have seen what I have seen,

And I have heard what I have heard.

So if to tears ye see me stirred,

Presume not that they spring from woe:

In thankful wonderment they flow.

Praise be to Him, the Lord, the King,

Who gives beyond all reckoning.

This mysterious and powerful allusion to that which Dr Lings has ‘seen’ and ‘heard’ is none other than the concomitance of the deep spiritual sincerity which he attained by God’s grace and which Dr Shah-Kazemi beautifully illustrated with a combination of extracts from Dr Lings’s writings, his lectures and teachings and small jewels of wisdom that Dr Shah-Kazemi witnessed in his everyday actions.

This was a lecture unlike so many lectures that are merely accounts of historical facts and theses. The very nature of the man demanded that the audience taste of the sincerity in question, directly. Just as Dr Lings spoke of how the saints drank directly from the fountains of divine mercy and grace that lie in Paradise, Dr Shah Kazemi transmitted to the audience the perfume of this concrete spiritual presence that he experienced in his contact with Dr Lings.

There was an almost cathartic effect on the audience, accompanied by gasps and sighs of inner joy and insight, as the greatness of a man that they may or may not have had the chance to meet in the flesh was remembered. By the end of the talk several of the audience were themselves in tears, but it was evident that these were not born of sorrow, but rather from that ‘thankful wonderment’ that Dr Lings himself mentions in his poem.

Dr Shah-Kazemi, paraphrasing Lings’s writings, summed up the experience, “when you are in contact with actualised perfection, that can have an actualising impact on your own soul — it can help you to bring to fruition the sanctity that is waiting to be realised within you.”

As Dr Shah-Kazemi remarked in his talk, one of the testaments to the greatness and legacy of Dr Lings is the influence he had on many people, not just during his lifetime, but even now after his passing. The lecture provided an opportunity to meet with some of the attendees, some of whom had come from abroad for the occasion. Dr Shah Kazemi personally thanked them at the beginning of his talk, remarking that they illustrated the strong magnetism that Dr Lings continues to exert on spiritual seekers.

This thought was echoed by another attendee, Slimane A. from Oxford. “The first thing that comes to mind when I think of him is his gentleness, his kindness. But as a spiritual master he saw in you what you needed most and he gave you that. There was a certain luminance to Shaykh Abu Bakr, especially towards the last years and months of his life and everyone perceived that. There was a kind of special gentleness for his spiritual children and even all human beings.”

Ovidio Salazar knew Lings for many years and worked with him to produce a film on his 1948 pilgrimage to Mecca. “I couldn’t begin to describe the immense influence he had on my life. He is someone who would constantly remind us of what we should strive to become.”

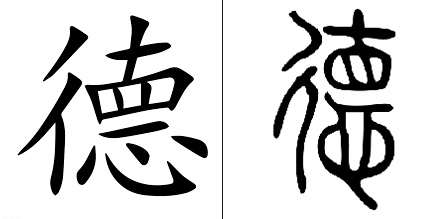

Other attendees spoke of the influence that Lings’s life and thought had upon themselves and the world. Keith Critchlow, co-founder of the Temenos Academy and lifelong lover of the traditional arts, summarised his thoughts on Dr Lings: “Dr Lings was the most extraordinary balance and mixture between one of my ideals as an English gentleman and an unfathomable Sufi, a man of faith. His particular contribution was to get twentieth century human beings to rethink what symbolism is and what it means because we’ve reached a stage where the media has reduced language to its lowest possible level.” Lings also had a deep impact on Critchlow’s inner life, “I learned from him the spiritual way of silence.”

For Sebastian Moro, an Argentinian student of neoplatonic philosophy, Lings and his teachers furnish a key to unlocking the true meaning of philosophia. “Perennialism helps me understand ancient philosophy much better than any academic point of view or approach. So when I cannot understand Plato or the neoplatonists, I read Guenon, Schuon and Martin Lings. Professor Shah-Kazemi is a representative of a living tradition, and that is why I came to this lecture.” This was an echo of the point that Dr Shah-Kazemi made during the lecture when he discussed Lings’s own adamant assertion about himself, “Lings is nothing without Schuon.”

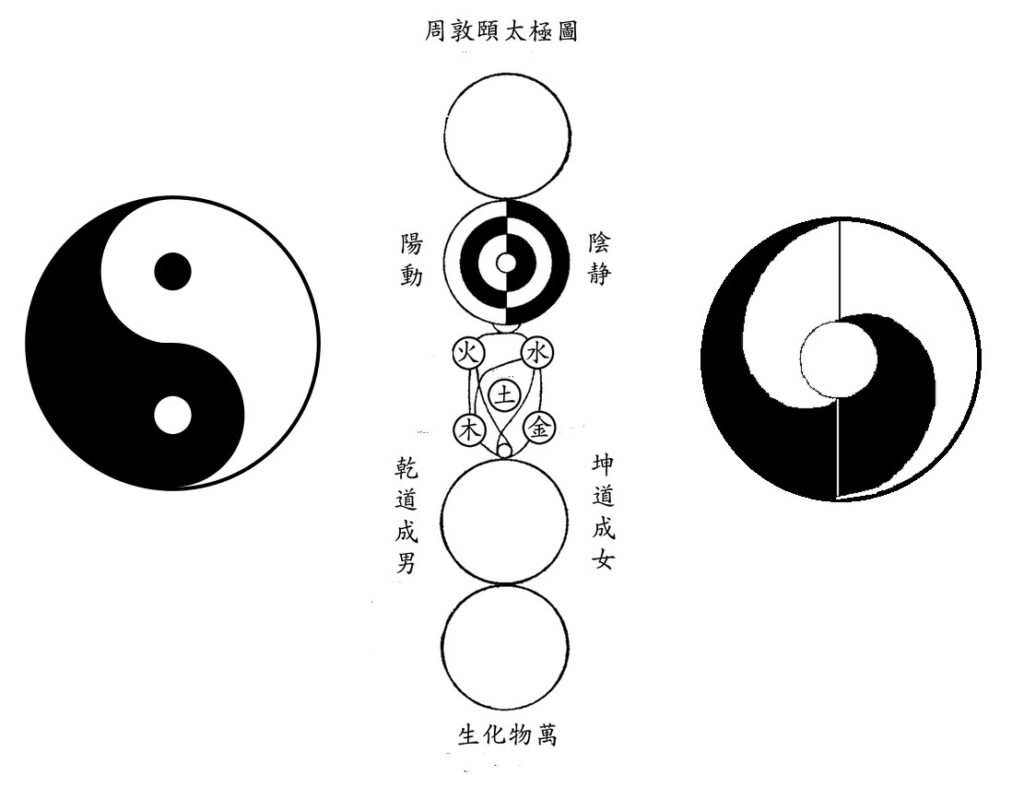

Another philosopher, John Varnes said, “ I’m primarily a student of Whitehead. When you look at other traditions you find many common elements and I’m trying to keep as open a view as possible —that’s the whole idea of Whitehead, not to consider anything outside a unity. There aren’t two —only one in the Universe.”

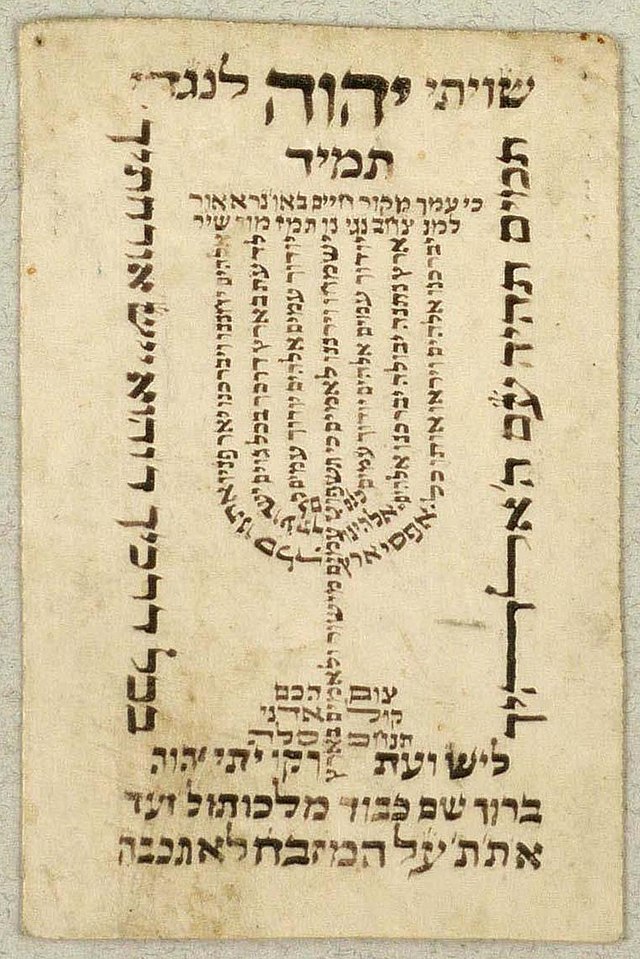

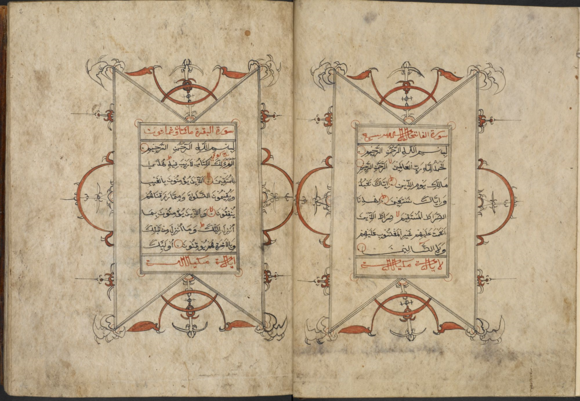

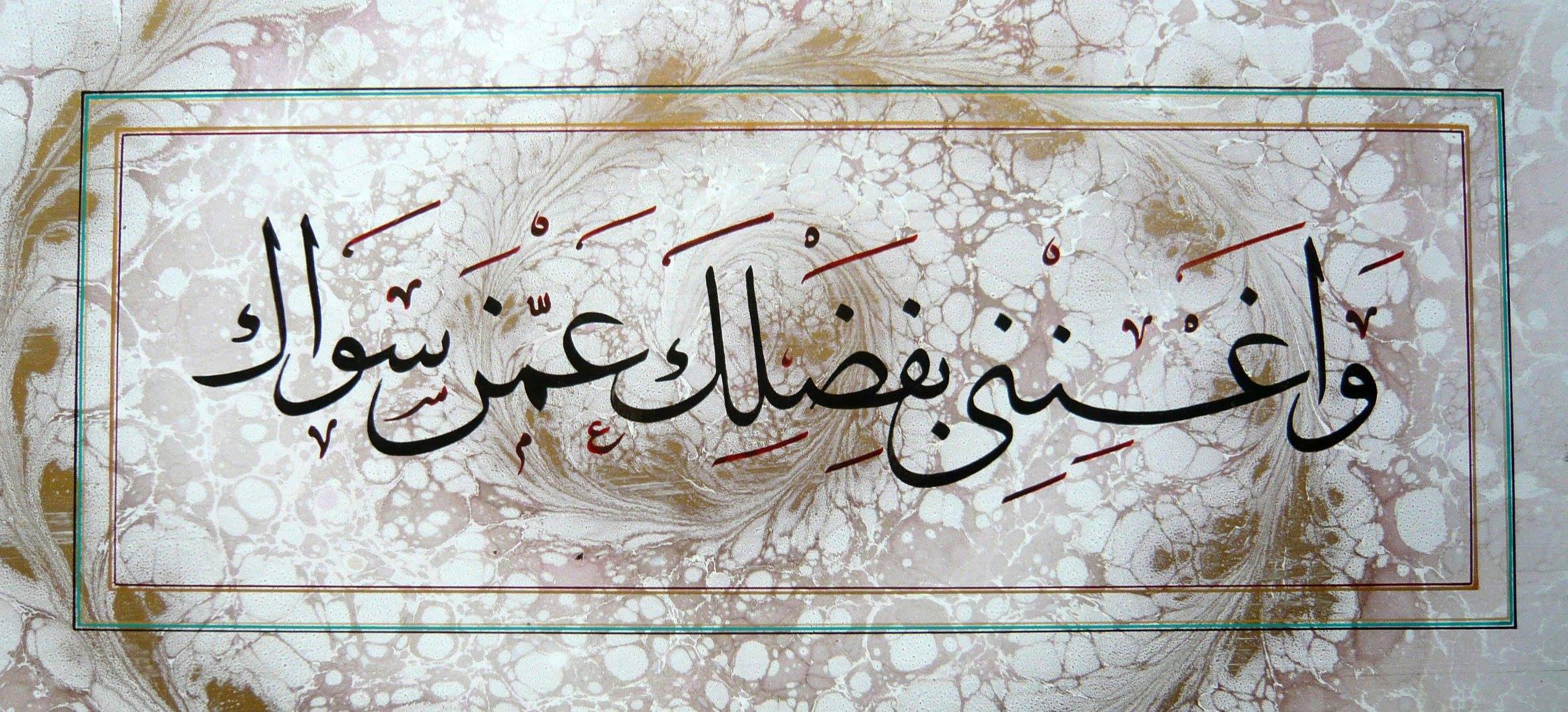

During the period of time when Lings was Keeper of Oriental Manuscripts at the British Museum, he had a great influence on the young Tajammul Hussain, an aspiring artist who, thanks to the guidance of Dr Lings, came to specialise in the nearly lost art of Quranic Illumination. “He was instrumental in helping me to develop my understanding of the art of Quranic illumination, which is what I now teach at the Ashmolean, based on the lectures he used to give. I attended every one of his lectures, even if it was repeated over and over again, because great truths would come out spontaneously.”

Others spoke of their personal encounters with Lings. For Justin Majzub, “the key thing that happened in my life was my providential meeting with Martin Lings. I heard his voice as he spoke to a young man who was asking questions on Islam. And just from those few moments hearing his beautiful voice, I was transformed, so to speak, melted down to the core. I was amazed to find out that this wonderful saintly Muslim didn’t live on top of a mountain somewhere in the Yemen, but actually lived in Kent and that I could actually have access to him. And that was the beginning of the most wonderful period in my life.”

Justin’s mother, Margaret Majzub, had the privilege of entertaining Dr Lings in her home during one of his trips with Justin. “I loved the man. He visited my house just once. He left an odour of sanctity in the house, literally. He had such a soft, lovely voice. I hear his voice in my ear now.”

Perhaps the most personal account came from Jean and Gerry Kittel, Dr Lings’s next door neighbours of over twenty years. Shortly after Lings died, Jean’s doctor discovered a serious tumour in her body and said she would have to go in for immediate surgery. “The x rays looked really awful —so awful that the doctor wouldn’t even stick a needle in me because he said it was too invasive. I went to Dr Lings’s grave and said to him, ‘I need some help here!’ I went in to have the operation and when I woke up, the doctor was standing next to me saying, ‘there’s nothing there!’ They really couldn’t understand it. It was pretty amazing. So we have been affected a lot by him. He was a lovely, lovely man, and we miss him.”

A recording of Dr Shah-Kazemi’s talk is now available through this link.

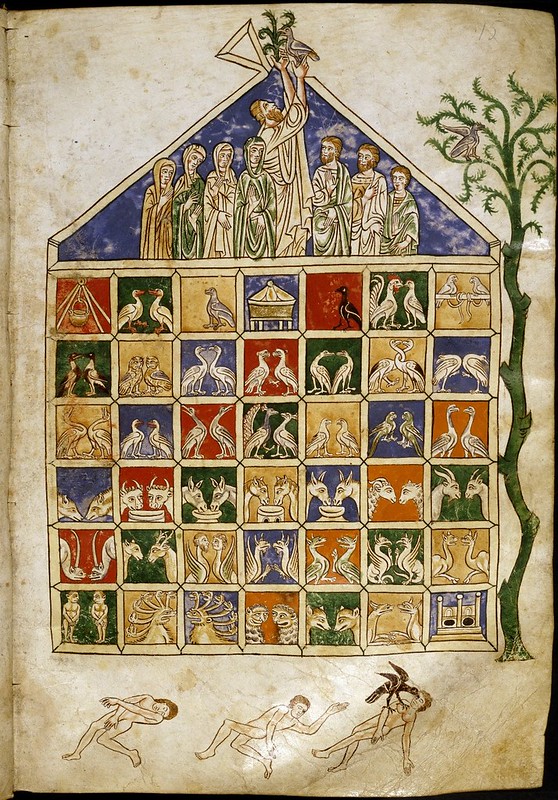

Flowers from the Florentine Codex.

Flowers from the Florentine Codex.